Diverting? Among other things, Krisi Smith’s World Atlas of Tea: From the Leaf to the Cup, the World’s Teas Explored and Enjoyed is definitely a fun and easy introduction to the topic it purports to describe. I would be lying if I said I learned a great deal from World Atlas of Tea, but the same would be true if I claimed to have learned nothing. To the aficionado (by which I mean anyone who’s been reading this blog beyond one or two entries), I’d be willing to say you can easily give World Atlas of Tea a pass and not be overly missing out. For the uninitiated, the issue is a little more complicated.

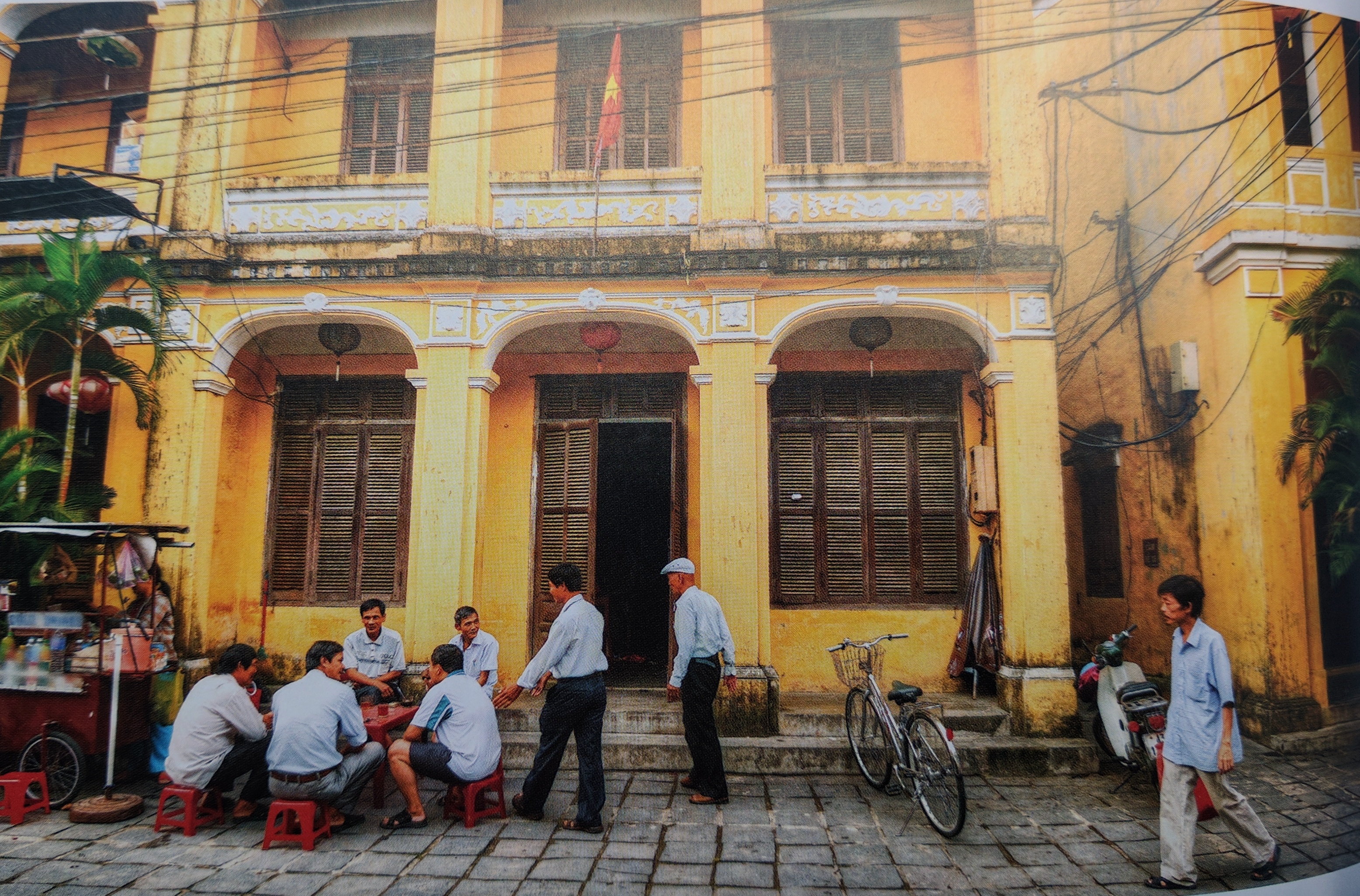

As a coffee-table book, Smith’s World Atlas of Tea succeeds quite brilliantly. It’s highly… “flippable”? The photography Smith has unearthed for each of the sections in her monograph are rare and engaging. Indeed, I’d be willing to state that among tea guides I’ve read and reviewed, World Atlas of Tea’s photos are possibly the most gorgeous and riveting. Sadly there are one or two photos I’ve seen elsewhere, especially those from Japan where tea farms are too busy and proprietary to offer up much in the way of unique photography for wide publication. Some of Smith’s archival images from the 19th Century colonial India and Sri Lanka actually made me weep in despair. In another case, Smith offers us a Tasting Wheel (page 98) more exhaustive than any I’d seen before. In truth, I wish I’d had access to it years ago for this blog. Frustratingly, despite almost 200 years of tea production in India, there remains a great deal of tea knowledge that simply doesn’t exist in translation.

The trouble is, as vibrant and engaging as it would otherwise be, World Atlas of Tea is too often inaccurate, opinionated and in some cases glaringly lacking. Some tea-growing countries such as Kenya and Turkey are given a great deal of description while others, just as important to the world market like Nepal and Indonesia are only very briefly described. Smith’s foci might reflect editorial choice (obviously books cannot be published unless they’re certain to sell), or her own interests, but in any case feel strangely unbalanced.

Perhaps because it’s an introductory text (for women?), a large portion of the content is spent describing tea preparation and mixology, especially surrounding hot fads like matcha, mate and even, yes, bubble tea that may be of interest to the Western novice getting her feet wet with tea. The tea-lover (or really anyone who’s actually dabbled with flavors and visited tea shops), looking for meatier dives into the history and breadth of the plant will be disappointed by World Atlas of Tea. There are a lot of maps included, some of which are even useful, but far from being cartographic in any real way, they serve only to act as pleasing coffee-table imagery.

Finally, I was stymied by Smith’s seeming inability to count. In the introductory remarks on page 13, Smith states, “For many years the oldest record of cultivated tea plants in China dated around 3000 BCE. However, fossilized tea roots recently discovered in China’s Zhejiang Province show signs of cultivation dating thousands of years earlier–to nearly 7000 BCE.” The recent discovery she mentions is described further in the China growing region section of the book on page 187 in the following way:

In 2004, scientists excavating at the foot of Tianluo Hill in the north of Zhejiang Province discovered ancient tea-plant fossils with marks indicating cultivation. These findings have shaken up all prior beliefs about the age of the tea industry. Previously the earliest recorded example of tea, which was also found in China, dated back to 3000 BCE. These remarkable new findings place the new date for the origin of tea cultivation at nearly 9,000 years ago.

I regret to inform you that I’ve done some fact-checking and to the best of my understanding the Tianluoshan excavation only puts the earliest date of tea cultivation at 3526 BCE . I have no idea where Smith might have found evidence of tea being cultivated in 7,000 BC; this number must be an example what’s now being called “alternative facts” (you can skip the rest of this paragraph if you’re uninterested in the discussion as it’ll get technical). In 7,000 BCE in Hunan, the Peiligang pottery and stone tools culture and the Jiahu culture of animal husbandry as well as one of the earliest evidence of rice cultivation (an excavation which also found the world’s oldest playable musical instrument) is exactly what one would expect from that era. The excavation at Tianluo mountain in Zhejiang that Smith refers to, describes the Hemudu lacquer wood and hunting and gathering culture which only dates from 5500 to 3300 BCE. She is correct that plant rhizomes were discovered there (in rows that indicate planting) in 2004, though only positively identified in peer review by a joint Tohoku/Kanazawa Daigaku Japanese archaeobotanical team as belonging to genus Camellia in 2008. They used a carbon-14 mass spectrometer to date the rhizomes to 3526-3366 BCE (with an 87.7 percent probability). If you add the current date of 2017 CE to earliest possible date of 3526 BCE you will have a summation of 5,543 years. In other words, the oldest possible evidence of tea cultivation by the Hemudu culture points to the industry being at most 5,500 years old, nowhere near 9,000… It’s actually fairly unlikely that more excavations on the East coast will corroborate this earliest evidence of tea industry as the furthest East ideal conditions for growing tea with Stone Age technology would have it tapering off in what is now Sichuan Province. Given that Zhejiang is on the East coast of China and that all other pre-history evidence of tea cultivation points to Yunnan on the Western border where many millennia-old tea trees still exist and Pu-erh and Yixing were developed, I fully expect future paleobotanical or archaeobotanical discoveries to point to dates much earlier than the well-established 2,737 BCE for the birth of tea in the Yunnan/Xishuanbanna/Northern Laos/Northern Vietnam/Northern Thailand area, perhaps even as early as 7,000 BCE. As of this writing, however, there is zero proof of that.

In summery, World Atlas of Tea is vibrant and interesting and concise, but far from being a comprehensive exploration of the subject. For the tea-loving bookworm, I would instead recommend either The New Tea Companion or the Tea Enthusiasts Handbook.